Teachers give students the grades they believe they deserve—but many are then pressured to change them by administrators, parents, and students themselves, according to Education Week.

About 4 in 10 teachers report receiving pressure in the last year from parents and students to change grades, and more than a quarter of teachers say they’ve received pressure from their principals. Only 20 percent of teachers say district leaders have exerted pressure related to grades.

Those experiences with grading come from the Education Week State of Teaching survey, which polled a nationally representative sample of 1,500 teachers in the fall. The results align with other research that teachers are more likely to feel more pressure from parents than school or district leadership to adjust students’ grades.

More affluent parents are more likely to exert that pressure, raising concerns about equity and fairness in student grades.

In a recently published study, Sarah Morris, a former teacher who studied grading practices while earning a Ph.D. in education policy at the University of Arkansas, analyzed five years of Arkansas student data to conclude that economically disadvantaged 9th graders in the state are twice as likely to fail a course than their more advantaged peers with the same abilities.

More affluent parents “have the luxury to complain,” she says. “They have the time to complain, to email their child’s teacher.”

The State of Teaching survey also polled a nationally representative sample of more than 650 school leaders and asked them to gauge the amount of pressure to change grades teachers at their school have received in the past year.

School leaders were less likely to say that they or other leaders at their school had placed pressure on teachers to change grades—86 percent said they’ve exerted “none” or “very little.” But 74 percent of teachers said they felt pressure from their principals.

One potential reason for the difference is that teachers might take even minor comments from their principals about grades as a form of pressure, since it’s coming from their boss, says Susan Brookhart, an education professor emerita at Duquesne University who has studied grading debates for decades. The results are colored by individuals’ perception, she adds.

“Pressure is a personal thing,” she says. “What’s a lot of pressure to you might be less pressure to someone else.”

Principals were also more likely than teachers to say that parents exerted pressure to change their children’s grades. That might be because parents often go directly to principals to complain about grades, bypassing teachers, Morris says. And principals might handle the complaint without involving teachers at all.

While the survey was of K-12 teachers, an analysis of the results showed secondary teachers were the most likely to receive pressure to change grades from parents, their students, and school leaders.

For instance, 83 percent of elementary teachers said they received no or very little pressure from their school leaders, compared to 70 percent of middle school teachers and 69 percent of high school teachers.

Seventy-five percent of elementary teachers reported receiving no or very little pressure from parents, compared to 55 percent of middle school teachers and 54 percent of high school teachers.

And 92 percent of elementary teachers reported receiving no or very little pressure from students, compared to 54 percent of middle school teachers and 37 percent of high school teachers. Twenty-eight percent of high school teachers said they received a high volume of pressure from students.

That’s no surprise, experts say. Once students are in high school, grades begin to matter more, factoring into things like selection for advanced coursework, athletic team participation, and prospects for college admissions.

Easing the pressure

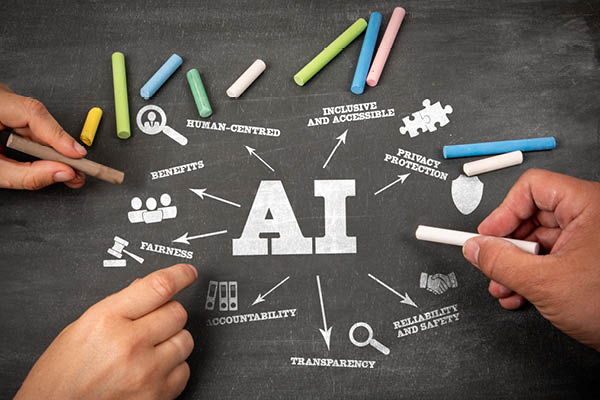

In recent years, school districts across the country have begun to separate what students know from other factors, like meeting behavioral expectations, in grades. Those types of grading systems are meant to encourage consistency and reliability—and they can also reduce the potential of teachers giving into pressure from parents or students, experts say.

“The grades are more defensible,” Brookhart says. “The grades are based on performance for academic tasks, and things like extra points for watering the plants or bringing egg cartons to school don’t factor into grades.”

That makes it easier for teachers to explain to a parent why their child got a certain grade, she says.

Says Morris: “It’s hard to argue with a teacher that they should change a score for a student when … they have their documents, and they have data.”

Education Week