As schools abandon textbooks for online and other alternatives, teaching and learning suffer, writes Robert C. Thornett in Education Next. He teaches humane letters and rhetoric at Chandler Prep, a Great Hearts classical school in Arizona.

“It is amazing how easy the Internet has made it to get books. Yet in this book-abundant moment, it is not unusual to see stacks of textbooks sitting uncracked throughout a school, he writes.

“Some schools do not bother buying books at all. ‘We like to give teachers freedom,’ school administrators have told me. Avoiding textbooks too often results in avoiding accountability, permitting unsound teaching ideologies, or being pennywise and pound foolish.

“Many school districts are touting their abandonment of textbooks as progress. However, schools often replace textbooks with disparate fragments of learning materials. Some are homemade lesson plans created by teachers. Some are found online (and) cobbled together into something approximating a cohesive course. Thousands of teachers unsatisfied with such resources spend hundreds or even thousands of dollars of their own money on personal textbooks and other materials to copy. There is a cost to ditching textbooks, and teachers often absorb it.

“Everything found in a good textbook—narratives, diagrams, art, maps, primary documents, homework questions—is carefully planned and organized by experienced authors and professional editors. Why stake the education of children on the assumption that scattershot, makeshift materials will be an adequate substitute for a textbook assembled by a team of experts?

“Abandoning textbooks can also throw a school’s curriculum into a tailspin. Sure, school systems publish curriculum outlines, but the hard part is creating teaching materials. Teachers—and students—have relied on the fact that state-approved textbooks are tailored to cover the state learning standards. Follow the textbook, and you can be sure you’re following the curriculum.

“Removing textbooks can force teachers to redesign their assessments without clear targets, hoping they are hitting benchmarks but never entirely sure.

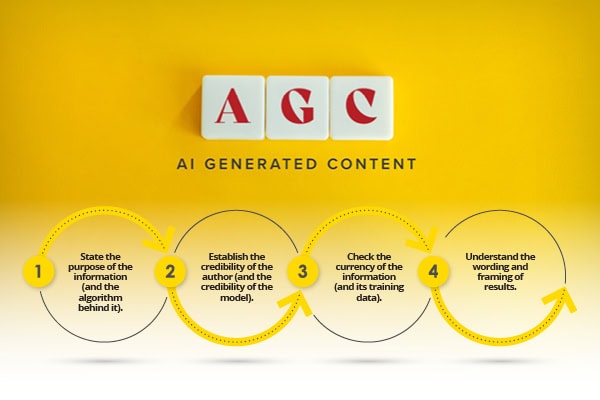

“Some publishers have shifted to e-books as a cost-effective way to deliver content. E-books eliminate printing and shipping costs, and they have a more global reach than printed textbooks. But the push for textbooks in a digital format is also driven by profit. E-books require buying new licenses each year, compelling customers to purchase access to online portals hosted by publishers.

“E-books… are usually cheaper and more portable. E-books have often bailed me out as a teacher when schools did not provide a physical textbook, turning what would have been a challenging year of scraping materials together into smooth sailing.

“But a 2018 study in Educational Research Review found screens have a ‘detrimental effect’ on reading comprehension that ‘increases over time.’ And e-books force screen-saturated students to spend even more hours in front of devices.

“Parents can demand that schools use textbooks. They should know which books are available in their child’s school and whether classes are using them. Parents’ nights or school open houses are a good opportunity for them to look around for books not being used and ask why not. If a fundamental purpose of schools is to instill in students a love of reading, putting textbooks back in their hands is a step in the right direction,” writes Thornett.

Education Next