Teachers still assign projects on anything from wolves and genetic engineering to drug abuse or the Harlem Renaissance, but the way students approach these assignments has changed dramatically, writes Dr. Steve Baule in eSchool News. Dr. Baule is a faculty member at Winona State University (WSU), where he teaches in the Leadership Education Department. Prior to joining WSU, Baule spent 28 years in K-12 school systems.

Students no longer simply “surf the web.” They engage with systems that summarize, synthesize and even generate research responses in real time, he writes.

In 1997, a keyword search could yield a quirky mix of werewolves, punk bands and obscure town names along with desired academic content. Today, a student may receive a paragraph-long summary, complete with citations, created by a generative AI tool scanning billions of documents. To an eighth grader, if the answer looks polished and is labeled “AI-generated,” it must be true. Students must be taught how AI can hallucinate or simply be wrong at times, Baule writes.

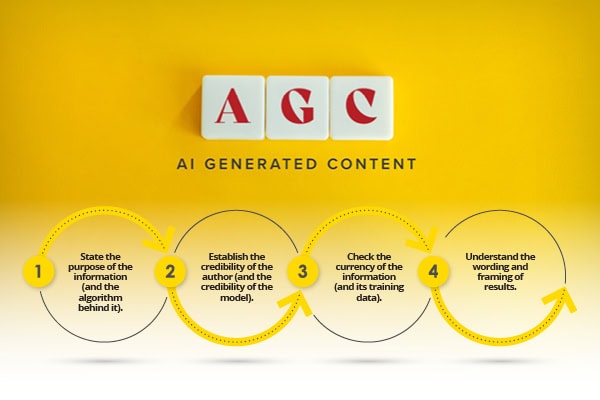

To help students become critical consumers of information, educators must still emphasize four essential evaluative criteria. These fundamentals now must be framed in the context of AI-generated content and advanced search systems.

1) State the purpose of the information (and the algorithm behind it)

Students must learn to question not just why a source was created, but why it was shown to them. Is the site, snippet or AI summary trying to inform, sell, persuade or entertain? Did an algorithm prioritize clicks or accuracy?

There is a need to know that didn’t exist pre-AI: • Was the response written or summarized by a generative AI tool? • Was the site boosted due to paid promotion or engagement metrics? • Does the tool used (e.g., ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity, or Google’s Gemini) cite sources, and can those be verified?

There is now a dual responsibility to understand both the purpose of the content and the function of the tool retrieving it is

2) Establish the credibility of the author (and the credibility of the model)

Who created this content? Are they an expert? Do they cite reliable sources?

Students must also ask: • Is this original content or AI-generated text? • If it’s from an AI, what sources was it trained on? • What biases may be embedded in the model itself?

Research often begins with a chatbot that cannot cite its sources or verify the truth of its outputs. This makes teaching students to trace information to original sources even more essential.

3) Check the currency of the information (and its training data)

When was something written or last updated? In the AI era, students must understand the cutoff dates of training datasets and whether search tools are connected to real-time information.

For example: • ChatGPT’s free version (as of early 2025) may only contain information up to mid-2023. • A deep search tool might include academic preprints from 2024, but not peer-reviewed journal articles published yesterday. • Most tools do not include digitized historical data that is still in manuscript form. It is available in a digital format, but potentially not yet fully useful data.

This time gap matters, especially for fast-changing topics like public health, technology, or current events.

4) Understand the wording and framing of results

The title of a website or academic article still matters, but now we must attend to the framing of AI summaries and search result snippets. Are search terms being refined, biased, or manipulated by algorithms to match popular phrasing? Is an AI paraphrasing a source in a way that distorts its meaning?

Students must be taught to: • Compare summaries to full texts. • Use advanced search features to control for relevance. • Recognize tone, bias, and framing in both AI-generated and human-authored materials.

Print, databases, and librarians still matter

It is more tempting than ever to rely solely on the internet, or now, on an AI chatbot, for answers, writes Baule. Just as in 1997, the best sources are not always the fastest or easiest to use.

Finding the capital of India on ChatGPT may feel efficient but cross-checking it in an almanac or reliable encyclopedia reinforces source triangulation. Similarly, viewing a photo of the first atomic bomb on a curated database like the National Archives provides more reliable context than pulling it from a random search result. Deepfake photographs proliferate the internet, requiring use of a reputable image database to be essential, and students must be taught how and where to find such resources.

Students can be encouraged to seek balance by using:

- Print sources

- Subscription-based academic databases

- Digital repositories curated by librarians

- Expert-verified AI research assistants like Elicit or Consensus

One effective strategy is the continued use of research pathfinders that list sources across multiple formats: books, journals, curated websites, and trusted AI tools. Encouraging assignments that require diverse sources and source types help to build research resilience, writes Baule.

Internet-only assignments are still a trap

Then as now, it’s unwise to require students to use only specific sources, or only generative AI, for research. A well-rounded approach promotes information-gathering from all potentially useful and reliable sources, as well as information fluency.

Students must be taught to move beyond the first AI response or web result, so they build the essential skills in:

- Deep reading

- Source evaluation

- Contextual comparison

- Critical synthesis

Avoid giving assignments that limit students to a single source type, especially AI. Instead, prompt students to explain why they selected a particular source, how they verified its claims, and what alternative viewpoints they encountered.

Ethics and integrity in the AI age

Generative AI tools introduce powerful possibilities including significant reductions, as well as a new frontier of plagiarism and uncritical thinking. If a student submits a summary produced by ChatGPT without review or citation, have they truly learned anything? Do they even understand the content?

To counter this, schools must:

- Update academic integrity policies to address the use of generative AI including clear direction to students as to when and when not to use such tools.

- Teach citation standards for AI-generated content

- Encourage original analysis and synthesis, not just copying and pasting answers

A responsible prompt might be: “Use a generative AI tool to locate sources, but summarize their arguments in your own words, and cite them directly.”

More critical than ever: the librarian’s role

Today’s information landscape is more complex and powerful than ever, but more prone to automation errors, biases, and superficiality. Students need more than access; they need guidance. That is where the school librarian, media specialist and digitally literate teacher must collaborate to ensure students are fully prepared for our data-rich world, Baule writes.

The fundamental need remains to teach students to ask good questions, evaluate what they find and think deeply about what they believe. Some things haven’t changed–just like in 1997, the best advice to conclude a lesson on research remains, “And if you need help, ask a librarian,” he writes.

eSchool News