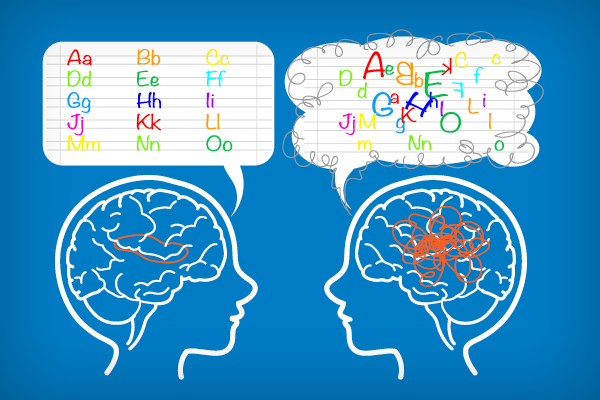

Most states have begun to require K-12 schools to use early screening to assess students’ risk for reading problems like dyslexia, according to an article in Education Week. Many states want all students to receive evidence-based literacy instruction to ensure reading proficiency.

But the idea that dyslexia can be cured, or “fixed” threatens these efforts and will continue to frustrate students with dyslexia and their teachers.

“Having been in the field for close to 40 years, I can tell you that dyslexia is a lifelong neuro-developmental disability that affects how the brain processes language—it has no cure,” explains Ben Shifrin, head of Jemicy School, a college-preparatory independent school in Owings Mills, Md. The school serves students with dyslexia and related language-based learning differences. “The good news is, though, with early intervention and with the appropriate types of modifications and intervention, people with dyslexia thrive in today’s world.”

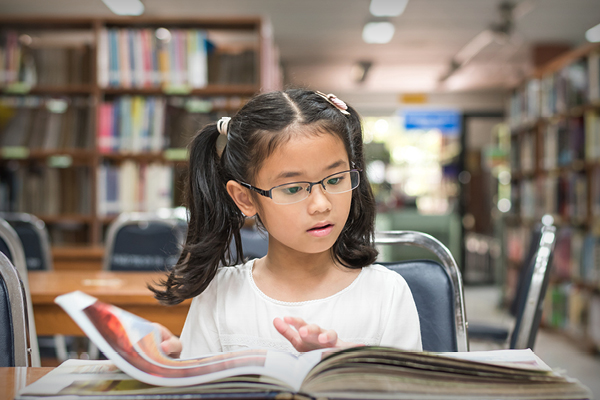

Making an accurate diagnosis as early as possible in a student’s K-12 journey is crucial, experts say, giving them the best opportunity to get help.

“When you catch dyslexia as early as possible, and provide structured literacy interventions with appropriate frequency, you can start to see the brain responding in as little as six weeks,” says Molly Ness, a reading researcher and literacy specialist with Sterling Literacy Consulting in Denver. She is referring to the brain’s optimal “neuroplasticity” period, which corresponds to when most children learn to read.

But most children with dyslexia don’t get diagnosed until at least 3rd grade. They miss the optimal time for appropriate intervention and their self-esteem can plummet.

Without early intervention, students tend to avoid reading because it’s hard for them, and they don’t like it. Without exposure to reading, their vocabulary fails to grow, as does their background knowledge, Ness says.

What are the long-term outcomes for someone with the disability?

“Most of the time, they won’t be as fluent as a regular reader, but they’re able to look at the written page and, within a reasonable amount of time, totally comprehend what’s on that page,” says Shifrin, at the Jemicy School. “A lot of times, dyslexics will tell you, ‘I know how to skim the page and read it for the main ideas, but I’m not reading every word.’”

They also learn perseverance.

“They’re used to failure. They know that if they don’t succeed the first time, there are many ways to approach a problem, and I think that’s why we see 33 percent of the Fortune 500 company CEOs having dyslexia,” Shifrin says.

Assistive technology, like audio books and text-to-speech or speech-to-text software, is making it easier than ever for dyslexics to get through school.

Learning to access compensation strategies such as assistive technology will help students with dyslexia manage, but not cure, their disability.

“It’s not a lifelong sentence, but it is a lifelong condition,” explains Ness. “You can compensate. You can improve.”

Education Week